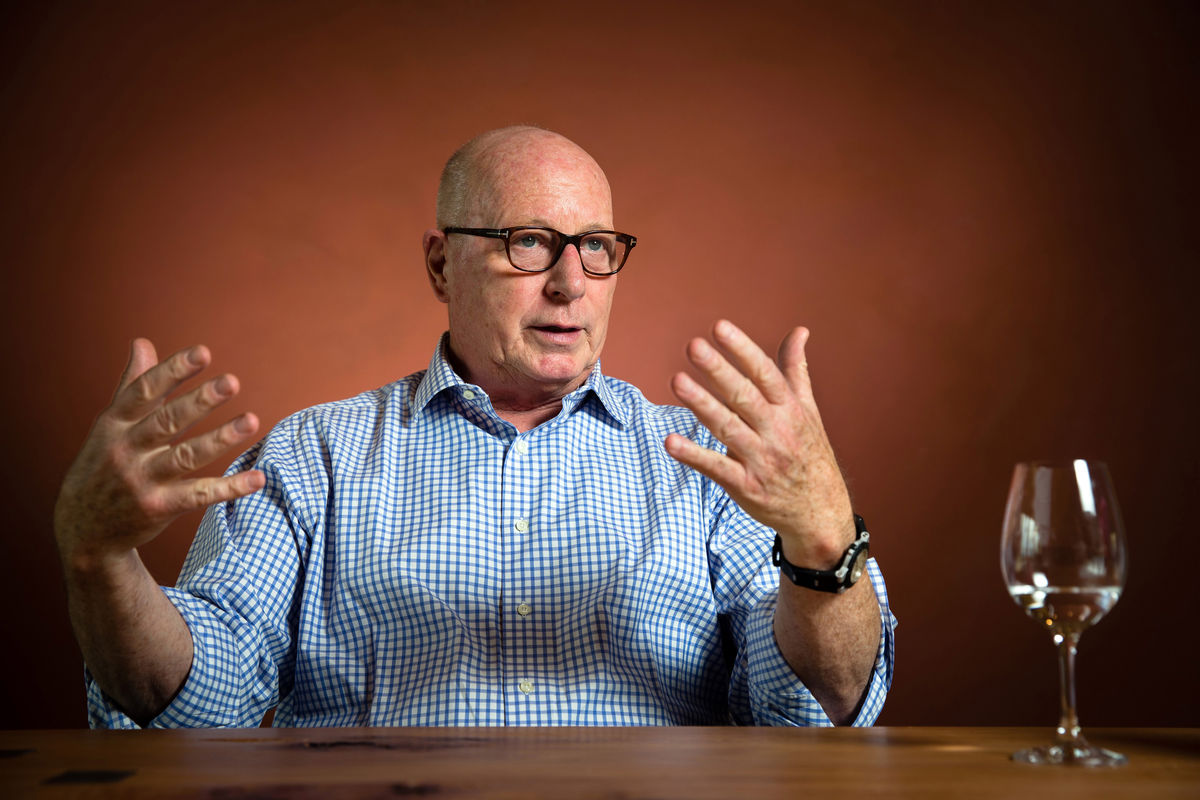

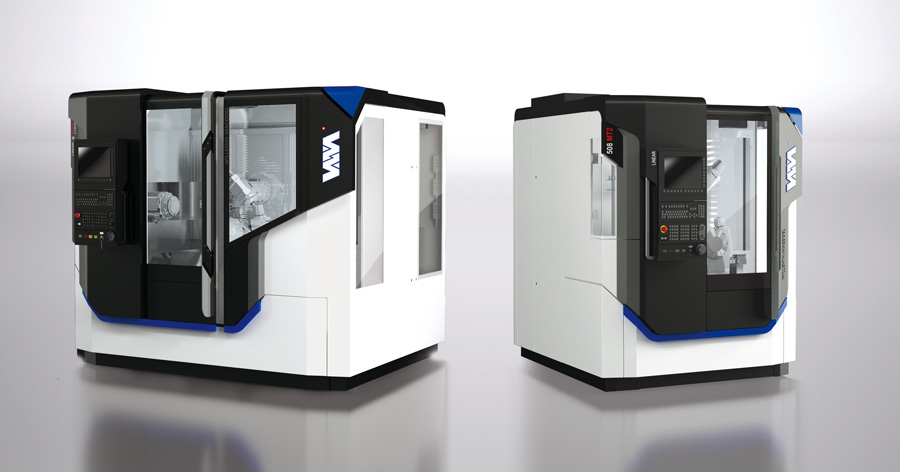

Thomas Schmidheiny inherited a cement company from his father that’s poised to become the world’s biggest. Yet what really excites the Swiss billionaire is a wine sideline with sales of about 0.1 percent of the cement revenue.

“If I could come back in my next life, it would be as a winemaker,” Schmidheiny said over coffee at Heerbrugg, his 12- acre vineyard that tumbles down the verdant hills flanking the Rhine where Switzerland and Austria meet.

Schmidheiny, 68, joined the family company at a Mexican subsidiary in 1970, became CEO of Holcim Ltd. in 1978, and inherited his father’s share in the business in 1984.

Since then, he has built Holcim, in which he’s the largest investor, into a global leader while increasing his wealth to $6.8 billion. Last month, Holcim and Lafarge SA announced a merger that would create the world’s No. 1 cement producer, with sales of $44 billion.

Schmidheiny has worked similar magic with his vineyards, albeit on far smaller scale. Using profits from his cement fortune, Switzerland’s fourth-richest person has created wine operations that span four continents. And though wine is his passion, he’s also a lifelong entrepreneur with little interest in running a business at a loss.

“I have a philosophy that the investments we make have to be profitable,” Schmidheiny said. “We have very few that are, in the long run, not profitable, and it’s the same with the wine.”

Cheval Blanc

As a bonus, the vineyards have helped him forge relationships with executives involved in the cement merger: Albert Frere, the largest shareholder in Lafarge, is part-owner of Cheval Blanc, a renowned vineyard in Bordeaux’s Saint-Emilion region. And Wolfgang Reitzle, the Holcim chairman who will oversee the merger, makes wine in Tuscany.

Schmidheiny’s family has as much of a history in wine as it does in cement. His grandfather founded a vine growers’ cooperative and his dad started making wine on the family’s Heerbrugg estate, where Schmidheiny remembers watching the grapes come in when he was a child.

“I grew up with the vineyard,” Schmidheiny said on a tour of the estate that’s home to the three-story white house he was born in, and where the heads of stags from his father’s hunting trips are still mounted at the entrance.

In 1979, Schmidheiny’s mother suggested investing in winemaking overseas, and the family bought the Cuvaison vineyard in California’s Napa Valley. The family later purchased Brandlin, a vineyard in the nearby Mount Veeder appellation known for its hearty cabernets. The wineries produced $11 million in sales last year, buoyed by premium labels.

Wine Lake

Though it took six years before the project produced a reliable cash stream, Schmidheiny said it’s now profitable. He produced 40,000 cases from 494 acres in California last year, with labels including Cuvaison Estate pinot noir at $38 a bottle.

His Australian venture, Chapel Hill near Adelaide, is still finding its legs. He says he overpaid for the winery when he bought it in 2000, just before overplanting in Australia led to what Schmidheiny calls “a lake of grapes.”

That “pushed prices down, and we were a victim,” Schmidheiny said. “But now it’s doing reasonably well in a difficult market. The lake is going down.”

Schmidheiny’s Australian sales totaled $6.2 million last year from 41,000 cases. Wines range from a sangiovese rose priced at about $14 a bottle to a cabernet sauvignon at $70. While the Australian operation is small, he said, it’s a challenge to oversee.

Motorcycle Trip

“For two day’s work, it’s a week’s travel,” Schmidheiny said. “We are not very happy about the results, but we are happy about the quality of the wine.”

Schmidheiny speaks most enthusiastically of his vineyard in Argentina. On a trip to South America 15 years ago, he traveled from Chile to Argentina by motorcycle and fell in love with the Andes foothills around Mendoza, Argentina’s premium wine region. He told his family office to buy land — a bare patch of hillside that he named Decero, or Spanish for “from scratch.”

“It’s the only place I know where you are the total master of your destiny,” he said of the vineyard.

The first vintage — reds made with Argentina’s signature malbec grape as well as cabernet sauvignon — came to market in 2008. Last year it sold 26,500 cases for about $2 million, and Schmidheiny says the venture “looks quite promising.”

Concrete Blocks

Despite his love of wine, Schmidheiny says he’s not looking for more “terroir” in another country. The merger of Holcim and Lafarge, he said, takes up most of his time.

He also says it’s unlikely another Schmidheiny will lead Holcim, though one of his four children might take over the vineyards. Among them is a son who co-founded Berlin-based film distributor DCM and a daughter who is building a brewery in Latin America.

“I believe we shouldn’t tie concrete blocks around the new generation,” he said. “The wine business, I can imagine someone will take care of. Cement is different.”

by: Patrick Winters

source: Bloomberg